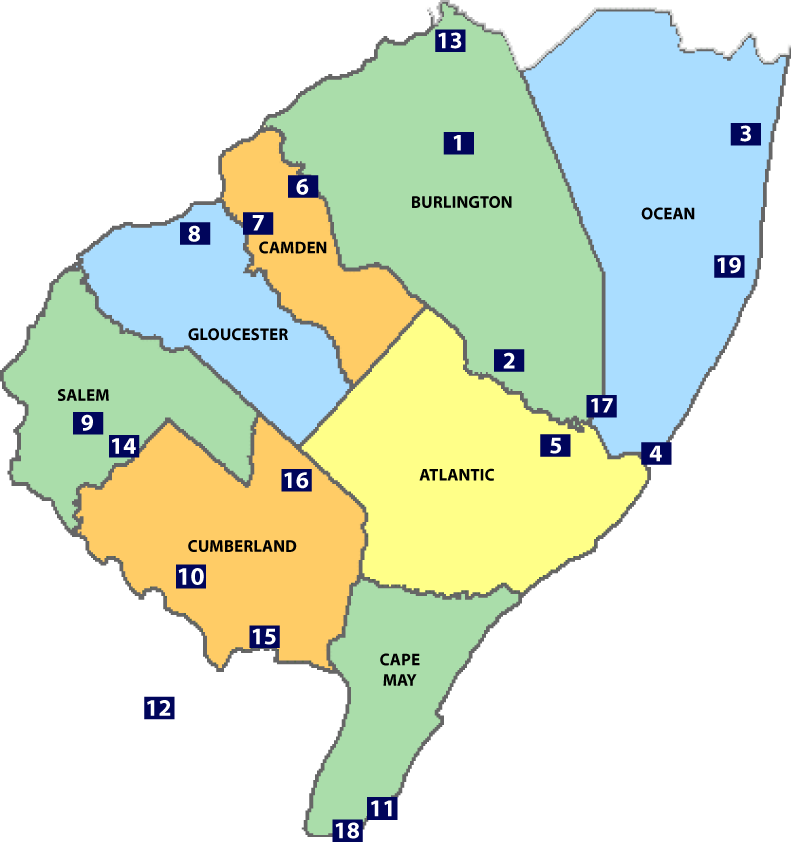

The importance of South Jersey and the often overlooked critical role played during the war is something the American Revolution Museum of Southern New Jersey aims to focus on. Battles fought throughout South Jersey include:

1. Battle of Iron Works Hill

2. Batso Village Ironworks and Munitions

3. Toms River Block House Raid

4. Privateers of Little Egg Harbor

5. Battle of Chestnut Neck

6. Coopers Ferry and Haddonfield (Generals Pulaski)

7. Battle of Gloucester (General Lafayette)

8. Battle of Fort Mercer (Red Bank)

9. Battle At Quinton’s Bridge

10. Greenwich Tea Party

11. Battle of Turtle Gut Inlet

12. Battle of Delaware Bay

13. Battle at Petticoat Bridge

14. Massacre at Hancock House

15. Battle of the Lower Maurice River

16. Battle of Bacon’s Neck

17. The Forks of the Mullica River

18. Privateers of Cape May

19. Cedars Bridge – last battle of Revolutionary War

Learn more about the Revolutionary War with these interactive audio tours of the Battle of Gloucester, Skirmish at Coopers Ferry, and British Evacuation of Philadelphia! You can take the tours remotely by clicking on the white arrow in the green circle above and then clicking on the story sites on the map. Or enjoy the tour on-site by downloading the TravelStorys app for free. The audio, text, and images will launch automatically as you approach each story site.

WAR COMES TO COOPER POINT

General William Howe’s British army began its occupation of Philadelphia on September 28, 1777, after defeating George Washington at the Battle of Brandywine. The British used Cooper’s Ferry as a landing for occasional military maneuvers in New Jersey. It was the closest New Jersey landing across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. American militia guarded and patrolled the Cooper’s Ferry during most of British occupation to monitor troop movements and enforce an American ban on the sale of food, livestock, firewood, and forage to the British.

General William Howe’s British army began its occupation of Philadelphia on September 28, 1777, after defeating George Washington at the Battle of Brandywine. The British used Cooper’s Ferry as a landing for occasional military maneuvers in New Jersey. It was the closest New Jersey landing across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. American militia guarded and patrolled the Cooper’s Ferry during most of British occupation to monitor troop movements and enforce an American ban on the sale of food, livestock, firewood, and forage to the British.

Attack on Fort Mercer

On October 21, 1777, two thousand Hessian troops led by Colonel Carl E. K. von Donop crossed the Delaware River on flat boats and landed at Cooper’s Ferry. Howe had granted Donop’s request to lead an attack on the American Fort Mercer at Redbank, New Jersey, a ten-mile direct walk south of Cooper’s Ferry. Cooper’s Ferry was chosen at the crossing site to avoid American vessels on the River between Kaighns Point and Red Bank.

Washington ordered troops to remain in and reinforced Fort Mercer and another fort, Fort Mifflin, on the opposite side of the Delaware River, after the occupation began. They were part of his plan to starve the British out of Philadelphia.

The forts protected a collection of underwater spiked obstacles anchored across the Delaware River between them called chevaux de frise or stockades, consisting of rows of large wooden spears tipped with sharp iron spikes and weighted down on the bottom of the river by heavy crates filled with rocks. They were designed to puncture the hull of any vessel passing over them and to prevent upriver movement of British ships bearing critically needed supplies for their army in Philadelphia. The Americans also had a small collection of armed sloops and schooners, and a flotilla of galleys called the Pennsylvania Navy defending the river and the stockades and blockading the supply vessels. Washington hoped the forts and barrier could be maintained until the Delaware River froze in the winter.

Donop’s command, including a two-thousand-man brigade made up of four companies of the Hessian Jager Corps, three battalions of Hessian grenadiers, the Regiment von Mirbach, and two guns, planned to march directly to Haddonfield. Less than half an hour away from the Delaware the brigade’s advanced party of light infantry ran into “an enemy party … which withdrew over Cooper’s Bridge towards Burlington.” The advanced party skirmished “with several hundred men on both sides of Cooper’s Creek” until about four o’clock in the afternoon allowing the rest of the regiments led by Donop to march to Haddonfield where they camped for the night.

At 3:00 A.M. the next day they started their march towards Fort Mercer. Donop had to change his planned route when his scouts reported that the bridge over Timber Creek was torn up. He led his troops with local guides on longer route from Haddonfield to Clements Bridge, passing through the villages now called Barrington and Runnemede, arriving at Red Bank shortly before noon.

With five British men of war in the river to support him, Donop believed he would capture Fort Mercer by day’s end. After his artillery launched a cannonade, one group of Hessians attacked the nine-foot-high southern wall of the fort, but the fort’s defenders drove them back by cannon and musket fire. Hessian grenadiers climbed the northern ramparts of an abandoned section of the fort but stopped when they reached a mass of felled trees with pointed branches designed to protect the fort’s main wall. They did not have the tools to remove them. Americans waiting for them on the other side fired away, and the Continental and Pennsylvania navies were able to fire cannon from the river along the long axis of the Hessian lines.

The attack failed. The Hessians retreated back to their camp ten miles away in Haddonfield. Donop was wounded in the thigh and was left on the battlefield by his retreating troops. Mortally wounded, he died three days later in the James and Ann Whittell House just outside the southern works of the fort. In all, the fort’s defenders killed eight Hessian officers and one hundred forty-three soldiers and wounded another two hundred sixty officers and men. The Americans lost fourteen killed and twenty-one wounded.

The attack failed. The Hessians retreated back to their camp ten miles away in Haddonfield. Donop was wounded in the thigh and was left on the battlefield by his retreating troops. Mortally wounded, he died three days later in the James and Ann Whittell House just outside the southern works of the fort. In all, the fort’s defenders killed eight Hessian officers and one hundred forty-three soldiers and wounded another two hundred sixty officers and men. The Americans lost fourteen killed and twenty-one wounded.

After resting in Haddonfield, the survivors marched back towards Cooper’s Ferry meeting British soldiers at Pomona Hall who had crossed over the Delaware River that morning to cover their retreat. All returned to Philadelphia through Coopers Ferry.

Howe changed plans and arranged to bombard Fort Mifflin into submission. He sent General Charles Cornwallis with two thousand men to attack Fort Mercer, after crossing the Delaware River three miles south of the fort at Billingsport. Colonel Christopher Greene decided to abandon the fort on November 20 to avoid having the garrison captured. On November 25, after levelling the fort’s ramparts, the British marched to Gloucester Town and shipped forage livestock to Philadelphia.

Washington’s plan to starve the British out of Philadelphia had failed with the loss of the two forts and the destruction and capture of the American warships once the stockade was removed. While Howe launched a feint at the American camp in Whitemarsh Pennsylvania in early December, he concluded that the American position was too strong. Howe retired to Philadelphia and Washington to Valley Forge for the rest of the winter.

Forage War – Arrest of the Coopers

By February 1778, both the Americans at Valley Forge and the British in Philadelphia were seeking to increase their depleted stores of provisions and forage. The British army had been comfortably quartered in Philadelphia, while many of Washington’s troops were starving during the winter, in part because Howe had sent out foraging teams to pick the country clean before Washington could do the same.

Overcoming his sensitivity of alienating Pennsylvania’s farmers, General Washington was forced to issue orders for a foraging operation, one of several by both sides, called the Grand Forage. After foraging in Pennsylvania, Major General Nathaniel Greene, the overall commander of the operation, ordered Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne and three hundred men to cross the Delaware River into New Jersey from Wilmington, Delaware, to destroy hay and collect all available livestock north and send it to Valley Forge.

With the help of vessels under the command of Captain John Barry, Wayne’s force crossed the Delaware and entered Salem County on February 19 and began scouring south Jersey for supplies, particularly cattle and horses. He collected one hundred fifty cattle and thirty horses. Gloucester County Clerk and army commissary Joseph Hugg accompanied Wayne to give receipts for the cattle taken and the hay burned. These receipts were of little value to farmers compared to British gold and silver.

Wayne arranged for Barry to burn four hundred tons of hay stacked along the Delaware River to distract the British away from him and to keep it out of their hands. Reaching Haddonfield on February 25, Wayne sent Washington a message stating that he was sending the livestock to Trenton and had heard that the British had sent two thousand troops into New Jersey.

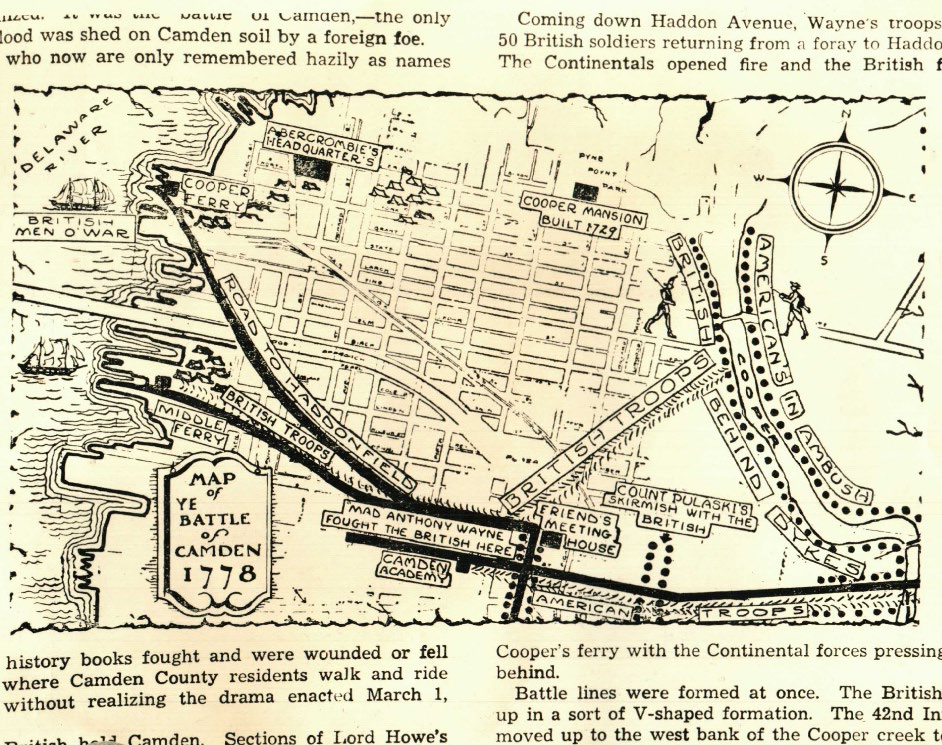

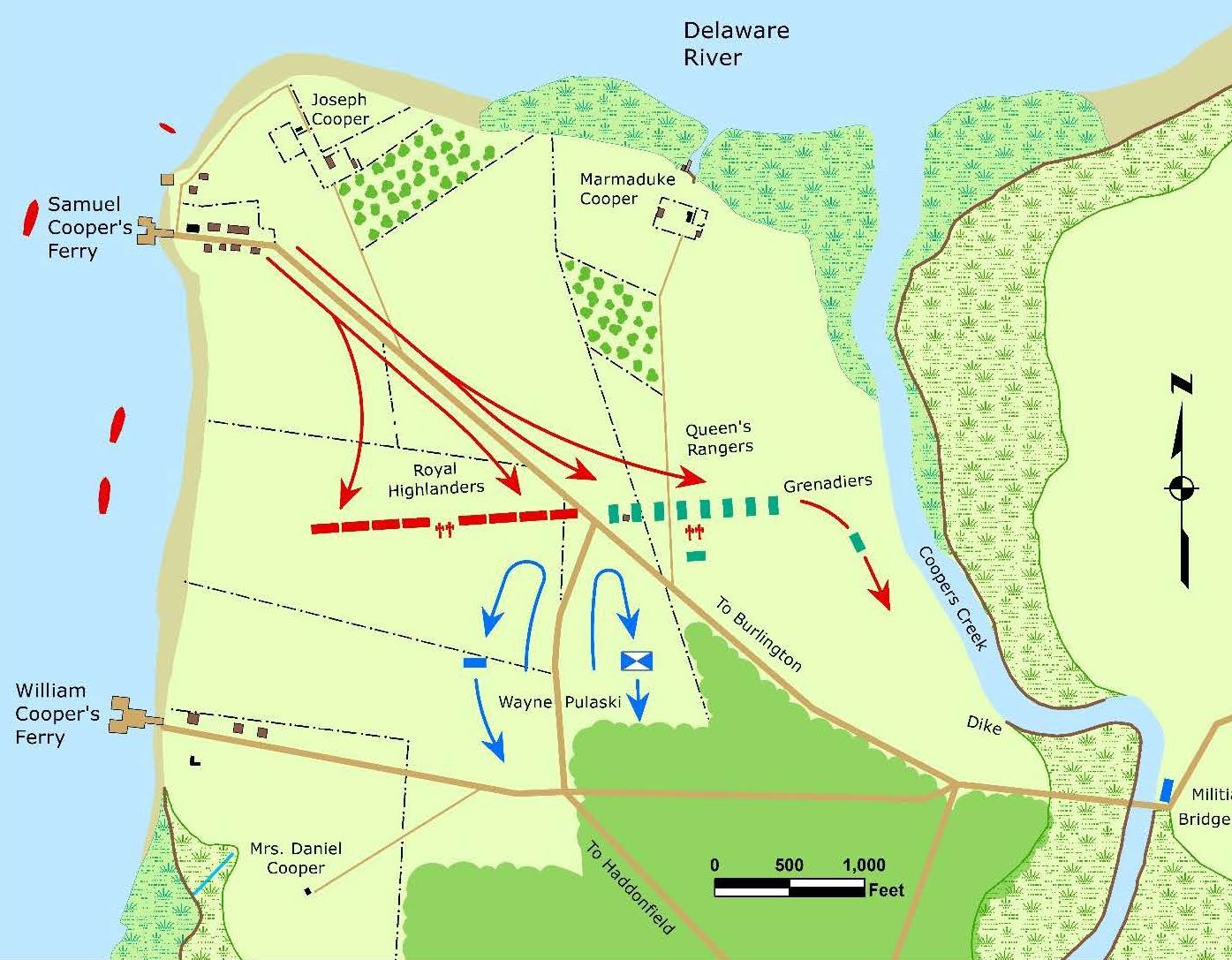

Howe had learned of Wayne’s expedition and sent two separate units to trap him and collect livestock and forage. Howe sent a light brigade under Lt. Col. Robert Abercrombie down the Delaware River to cross over at Billingsport, New Jersey, late on February 24. On the evening of February 25, a second contingent, commanded by Lt. Col. Thomas Stirling, consisting of the 42nd Regiment, the Queen’s Rangers, and four pieces of artillery (approximately one thousand men) crossed from Philadelphia to Cooper’s Ferry. After establishing a strong guard at Cooper’s Ferry, the bulk of the 42nd and Queen’s Rangers headed to Haddonfield. A detachment of British soldiers under Colonel Markham also passed over the Delaware the next day and took post at Cooper’s ferry and foraged nearby.

The British arrested Benjamin Cooper’s sons, Joseph and Samuel, and kept them prisoner in Haddonfield for two days. At the time of their arrest, Joseph was living in the Benjamin Cooper House, and Benjamin lived nearby at the ferry he had operated until the British occupation of Philadelphia. On March 5, Samuel wrote to a friend complaining that the brothers’ “…wives never knew where we was gone till just before we came home.” The brothers were released, but Samuel was arrested again later on suspicion of providing intelligence to the Americans. The British released him again but confiscated his spy glass.

A New Jersey Militiaman spotted Stirling’s troops on the march to Haddonfield and warned Wayne who quickly left the town for Mount Holly.

Having missed Wayne, Stirling’s contingent spent the night in Haddonfield. The next day Stirling ordered the Queens Rangers to scout south. They captured 150 barrels of tar and shipped it off to the British navy in Philadelphia, seized a large cache of rum and tobacco, and gathered cattle before returning to Haddonfield.

When Sterling learned that Wayne had reinforcements and was heading back to Haddonfield. he ordered his units to return to Cooper’s Ferry. Wayne sent an urgent request for help to Brig. General Casimir Pulaski at Trenton, New Jersey. Pulaski and his cavalry met up with a portion of Wayne’s soldiers. As the British were leaving Haddonfield, a Pulaski scouting force launched an attack on the Queens Rangers’ picket at Kay’s Mill nearby. The attack failed. The Rangers were prepared having received an advanced warning from a local loyalist. The skirmish did however cause the British to abandon much of their forage and hasten their march back to Cooper’s Ferry.

The night was extremely cold with sleet falling the whole way from Haddonfield to Cooper’s ferry. According to Ranger commander Major John Graves Simcoe, barns and forage occupied the ground for their encampment near the ferry requiring the soldiers to pass the coldest night many had experienced till then without a fire. Simcoe also wrote years later that some of his troops lit fires against his orders and accidently burned Joseph Cooper’s barn.

Wayne, with part of his force, Pulaski, and militia Colonel Joseph Ellis arrived south of Cooper’s Ferry on March 2. They planned to skirmish with the British, hoping to lure them away from the protective cover of the British navy guns. The British refused battle and drew up in a defensive line in front of the ferry and the Benjamin Cooper House. Stirling placed the 42d regiment on his right, Colonel Markham’s detachment in the center, and the Queen’s Rangers on the left and ordered the rest of his soldiers to embark to Philadelphia with their horses on the flatboats. When Wayne’s forces did not advance, Colonel Markham’s detachment boarded the boats. Stirling’s troops were halfway over the Delaware when Wayne’s forces attacked. Simcoe surmised that Wayne’s men attacked when they saw smoke from Joseph Cooper’s burning barn taking it as a signal that most of the British had left.

Stirling ordered the 42nd regiment and Queens Rangers to march forward in line but not beyond the protective range of British naval guns. The Rangers’ grenadiers secured the British left by lining up along a dike on the Cooper River’s west side when Ellis’ militia came into view on the opposite banks. Moving forward Simcoe’s Rangers pushed Pulaski’s cavalry back into the woods. When about a hundred militiamen appeared near Cooper’s Creek Bridge, Simcoe sent a grenadier company and fired his three-pounder cannon at them. The Rangers’ attempt to force their way over Cooper’s Bridge failed. But as the New Jersey militia were busy destroying the bridge and posed no threat to the British left, Simcoe left them alone.

With British naval gunfire from ships, cannon fire from field pieces, and fire from musketry now become general, Wayne’s forces withdrew recognizing that they could not draw Stirling beyond his support from the ships. Firing totally ceased around 6 p.m. Wayne’s advanced units withdrew to a safe distance. By the time Wayne’s main force arrived, it was getting dark. The Highlanders and Queen’s Rangers pulled back to the ferry, embarked, and were in their Philadelphia quarters by nine o’clock. Simcoe reported several men wounded and one dead.

Plunder of Haddonfield

On March 19, Washington ordered Colonel Israel Shreve and his regiment to New Jersey to protect the Delaware River coastline and the salt works along the seacoast. He had learned that Howe intended to send four regiments down the river to collect forage and cattle in Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May Counties. If the British did not land in New Jersey, Washington instructed Shreve to collect cattle from Salem and Cumberland Counties with “Col. Hug, the Commy of purchase” to “attend him and settle for the cattle.”

On March 28, Shreve wrote to Washington that New Jersey Governor Livingston had asked him to join Ellis at Haddonfield and wait until reinforced with militia. He reported that they had arrived and that he then had, besides his own regiment: “170 militia infantry, 20 militia horse, and 35 militia artillery with two three pounders.” He stated that “four British regiments, consisting of between 1,000 and 1,200 soldiers,” commanded by British Col. Charles Mawhood, were in Salem, that “all the country on the River, between Salem and Haddonfield, is open to the Ravage of the Enemy,” that “150 tories are in arms fortifying at Billingsport,” and that “a great number of Disaffected Inhabitants are trading with the enemy.”

Shreve asked Washington for additional troops to “quell the tories and collect a considerable quantity of provisions which otherwise will fall into the hands of the enemy.” He said, “this country is in miserable situation the inhabitants afraid of every person they see” and that he would “do all in his power to protect the virtuous inhabitants and suppress the tories.”

After receiving intelligence on Shreve’s status, Howe sent the six hundred Light Infantry Brigade under Lt. Col. Robert Abercrombie across the river late on April 5, landing at the Gloucester Town ferry about 1 a.m. According to later reports by several British deserters, Abercrombie had given his troops orders to show no quarter and to plunder Haddonfield for encouraging opposition to the British.

Near Gloucester Point the British captured three of the four militia sentries, with the fourth escaping to ride his horse through Newton Creek and arriving at Haddonfield at half past two in the morning to warn of a British attack.

Shreve and Ellis quickly evacuated Haddonfield after sending warnings by messengers to Woodberry and Cooper’s ferry. Coopers ferry was guarded by forty militia men and two riders. Shreve’s warning included instructions for the Cooper’s ferry guards to make a retreat over the Coopers Creek Bridge.

Ten minutes later, the British light infantry arrived in Haddonfield, and after a signal, gave three “Huzzays” and “immediately stove open the doors, wounded several inhabitants,” broke into every house, and plundered the town. As they marched for Cooper’s Ferry, the British set two houses owned by Quakers, ablaze. One belonged to Thomas Redman, Chairman of the Haddonfield Friends Meeting, a pacifist who had spent eight weeks in jail at Gloucester Town for his opposition to the war.

Miles Sage, the messenger Shreve had sent to warn the Cooper’s Ferry guards, returned to Haddonfield just as the British entered the town. British soldiers stabbed him in various places and left him for dead in the street. A Scotch officer ordered him to be carried to a small building where he was attended by a surgeon of the army who found thirteen bayonet wounds. He survived.

In response to Sage’s warning and Shreve’s orders, militia Lt. Stout got the guards together at Cooper’s Ferry and retired over the bridge as ordered. However, his superior, Major William Ellis (2nd Battalion Gloucester Militia) “imprudently” ordered him and the guards back to their post at Cooper’s ferry. The British attack cut off any retreat.

The British overwhelmed them, killing eight men, some by bayonet, and capturing thirty-seven. Some broke through the British lines. Some were killed in Cooper’s Creek, while others escaped by swimming across it.

The British crossed the Delaware to Philadelphia shortly thereafter.

Firewood Expedition and Fortification of Cooper’s Ferry

The British garrison and civilian population in Philadelphia were running out of firewood by April 1778.

On April 28, Howe’s chief engineer, Captain John Montresor, and his quartermaster general went over to Cooper’s Point with six hundred troops to survey its woods.

On May 3, 1778, two British regiments crossed to Cooper’s Ferry and began constructing redoubts (small forts) that would protect the wood cutters. A few days later two small Loyalist units joined them. Then, daily, two hundred men arrived from Philadelphia to cut firewood for the British.

Washington responded by sending the 1st New Jersey Regiment to join Shreve and prevent the Cooper’s Ferry garrison from foraging. Apart from a few skirmishes and the near capture of Brig. General William Erskine, there was little military activity at Cooper’s Point after the wood cutters departed. It proved to be the calm before the storm.

Philadelphia Evacuation

Encouraged by the Americans’ victory at Saratoga, France and the young United States of America signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce on February 6, 1778. As the British government contemplated a looming world war, they realized that they would have to redeploy troops from North America to protect their valuable colonies in the West Indies. Philadelphia would have to be evacuated. These orders arrived in Philadelphia May 8; the same day—on another ship—a new commander-in-chief arrived, Sir Henry Clinton.

On June 1, the British began moving wagons and provisions to Cooper’s Ferry. Infantry and field artillery began crossing on June 14. By June 15, British, Loyalist, and Hessian soldiers lined the road from Cooper’s Ferry for three miles east towards Haddonfield. Three thousand men disembarked Cooper’s Ferry on June 16. They too marched towards Haddonfield. In just four days about ten brigades of infantry, about 11,000 men had crossed the river. The occupation of Cooper’s Ferry devastated the areas gardens, fields and woods as equipment, baggage, provisions, horses, and thousands of men poured into and out of Cooper’s Ferry. Their tents having been stowed on ships, some soldiers made brush shades for protection from the sun. By the end of the June 17, the column of waiting soldiers stretched to Haddonfield.

Samuel Cooper observed to his friend that he was

In the midst of trouble & confusion, locked up in my room, which is the only place with my Kitchen I have left to make use of, —the rest being all taken up with officers … I know you must feel for my Distressed Situation which is shocking and grows every day ten times worse. My house is surrounded with near five hundred Waggons and tomorrow the Horses will come, next Day the Army. Tomorrow the Shipping is all to be gone by sunset. When you come Down, which I hope will be next week, you will see Destruction such as will shock you [sic].

By June 18, the British were gone on their way to Sandy Hook by way of Monmouth Court House. Samuel Cooper’s Ferry and Joseph Cooper’s house were no longer in a war zone.